By: Nico Mjones, Student in Applied Linguistics MA and Certificate in Curatorial Studies / CLM Intern

June is Pride Month in Canada. As both a student of Applied Linguistics and a member of the LGBT community, I find it important to talk about the ways in which language matters for LGBT people. In this blog I will discuss some of the ways in which language and LGBT topics intertwine. The way LGBT topics and identities are talked about, the terms used to refer to LGBT people, and even grammatical issues such as pronouns and grammatical gender are some of the ways LGBT people and language intersect. Due to Canada’s diverse linguistic make up, these matters can vary by language as well, including in official languages, non-official languages, and indigenous languages.

Terminology

Terminology is very important to LGBT people. The words used to refer to different LGBT identities and to the community collectively have evolved significantly over the last century. The term LGBT, “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender” is the most common collective term, but LGBTQ+, “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer/Questioning, Plus” is often used in an attempt to be more inclusive. LGBT terminology in Canada is similar to that in the rest of the Anglosphere and Francophonie. A term that is more common in Canada than in other countries is the term “Two-Spirit”. Two-Spirit is a collective term for the many different pre-colonial gender and sexuality concepts in Indigenous cultures in Canada. Not all of the indigenous groups in Canada have traditional identities that fall within the Two-Spirit moniker, and not all Indigenous people identify with the term in preference to other LGBT terms. Many LGBT organizations across Canada have begun to include Two-Spirit so as to be more inclusive of Indigenous LGBT people. An example of this is the longer acronym LGBTQ2S+, adding “2S” to represent Two-Spirit in the acronym.

In English, there is debate over the term “queer”. Once universally considered a slur against LGBT people, today many consider the word “reclaimed” and many LGBT people use it self-referentially and to refer to the LGBT community. Some prefer the term ‘queer’ as more succinct, radical, or inclusive than LGBT. Others consider the term to be too offensive and harmful to be used.

Pronouns and Grammatical Gender

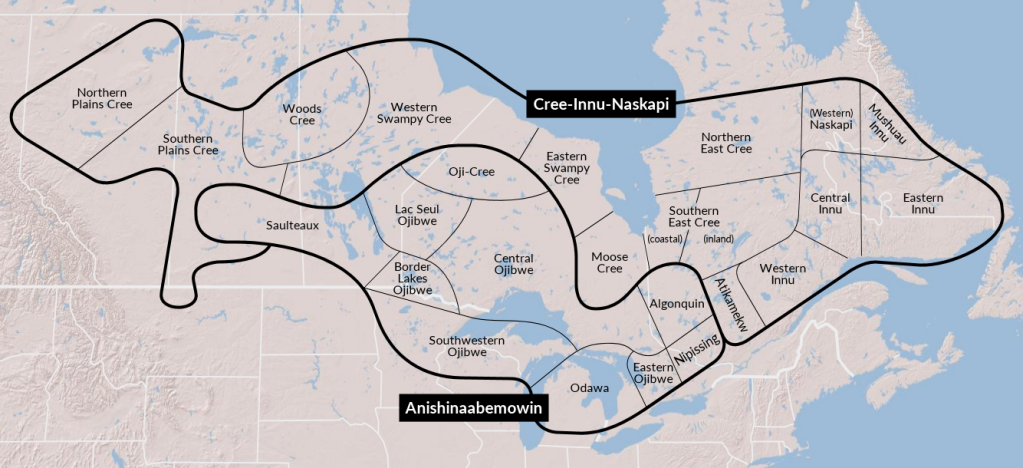

Gender in language is an especially important subject for transgender and non-binary people in the LGBT community. Grammatical gender is a system for dividing nouns into different classes and varies between languages, For example, French divides all nouns into two classes of masculine and feminine, while Algonquian languages divide all nouns into two classes of animate and inanimate. Generally, a noun’s class affects other words in the same sentence, through agreement on verbs, adjectives and pronouns. The LGBT community is particularly focused on neutrality in pronouns. Most trans people have preferences for their pronouns, and these can be different from what are assumed, Non-binary people may prefer neutral pronouns.

For English in Canada, gender neutrality is relatively easy. English does not have grammatical gender outside of gendered pronouns. Many gendered terms, such as actress or waitress, have declined in use and terms like actor and waiter have become gender neutral. There has been some debate over a neutral pronoun. Most commonly used is the singular case of “they”. Some view this as grammatically incorrect, but the usage of singular they has been documented in English since at least the writings of Shakespeare. Singular they has become very commonly used amongst non-binary people in the LGBT community, andsees some acceptance by style guides and other prescriptive sources. There have also been examples of inventive neutral pronouns, such as “xe”. These are attempts to create a new pronoun that is gender neutral, and these have seen some usage but relatively little acceptance in linguistic prescriptive guides.

Gender neutrality in French in Canada is considerably more difficult because of its system of grammatical gender. This makes it difficult for non-binary people who may wish to have gender neutral language used for them. For pronouns, “iel” is the most commonly discussed gender neutral pronoun in French. There are many people who are actively working to develop a system of gender neutrality in French. In Canada, one significant academic is Florence Ashley, a doctoral student at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Law. Florence Ashley, who themself uses gender neutral pronouns, specializes in research of transgender rights and welfare in Canada, and has also written in French about developing a system of gender neutrality in the French language.

Indigenous & Immigrant Languages

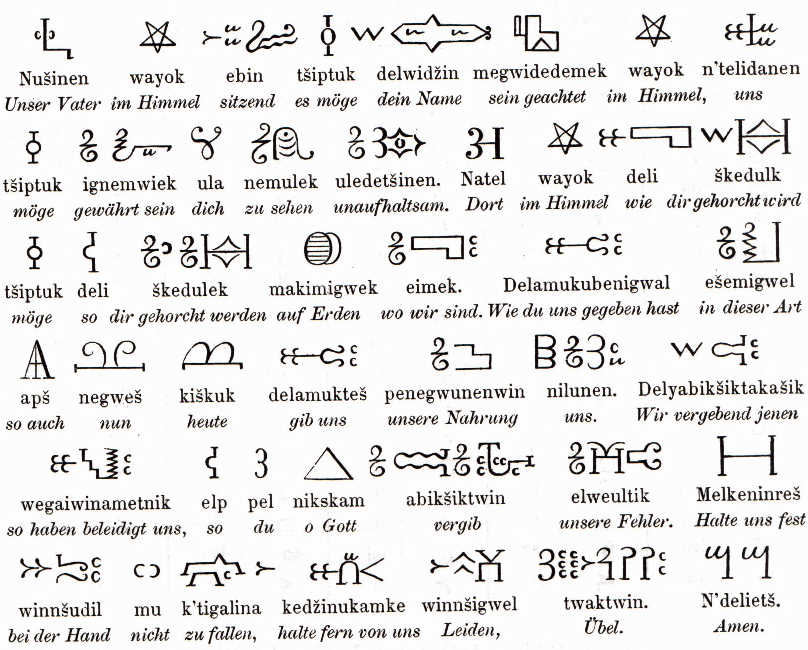

Pronouns and grammatical gender in Canada’s non-official languages vary considerably. Many indigenous languages in Canada have a single gender neutral pronoun, such as the Cree 3rd person pronoun “wiya” which is not differentiated by gender. Many indigenous languages have a system that is not defined by masculine and feminine, but instead by animacy and inanimacy. This system is found in the Algonquian, Iroquian, and Siouan language families, which include the Cree, Anishnaabe, Mohawk, and Nakoda languages, among others. Because the grammatical gender in these languages is based on animacy rather than on masculine and feminine, they have no impact on the gendering of language for LGBT usage. Other language families, such as Na-Dene or Inuit, do not have grammatical gender at all.

The many iImmigrant languages in Canada also vary greatly with respect to grammatical gender. The Chinese languages, the largest in Canada after English and French, do not have grammatical gender and have a single gender neutral pronoun in speaking. The third person pronoun in Chinese is written differently for “he” or “she” but both are pronounced the same. In Mandarin this is “Tā” and in Cantonese “Keoi”. Languages like Persian and Tagalog, both within the ten largest languages spoken in Canada, have no grammatical gender and no gendering in pronouns at all.

Other immigrant languages share some of the difficulties that French presents. Spanish, a Romance language related to French, is the third largest non-official language in Canada. Spanish is a gendered language similar to French, but gender neutrality has been more easily developed for it. Gender neutral endings for nouns are a frequent subject of discussion amongst Spanish speakers in Canada, the US, and Latin America. Where traditionally words would end in “o” for masculine or “a” for feminine, the endings of “x” or “e” are used to create gender neutrality. An example is “Latino/Latina/Latinx/Latine”. There is considerable debate about the “x” and “e” endings, but many Spanish language organizations in Canada and abroad have come to accept or promote the usage of “x” and “e” endings for gender neutrality.

Some languages have borrowed gender neutral pronouns from other languages. In German, the eighth largest language in Canada, the English gender neutral pronoun “they” is frequently used. The Scandinavian languages Norwegian and Swedish have attracted attention for borrowing the gender neutral third person pronoun “hen” from Finnish.

| Grammatical Gender | Gendered Pronouns | Gender Neutral Pronoun (if known) | |

| English | No | Yes | They, Xe, Others |

| French | Masculine/Feminine | Yes | lel |

| Chinese | No | No | Tā (Mandarin), Keoi (Cantonese), others |

| Punjabi | Masculine/Feminine | No | Uha |

| Spanish | Masculine/Feminine | Yes | Elle |

| Tagalog | No | No | Siya |

| Arabic | Masculine/Feminine | Yes | Huma (From Koranic, dual form) |

| German | Masculine/Feminine | Yes | They (Borrowed from English), Xier, Es (equivalent to “it”), use of name |

| Italian | Masculine/Feminine | Yes | Loro (equivalent to they) |

| Hindustani | Masculine/Feminine | No | Vah |

| Portuguese | Masculine/Feminine | Yes | Elu |

| Persian | No | No | U |

| Cree | Animate/Inanimate | No | Wiya |

| Ojibwemowin | Animate/Inanimate | No | Wiin |

| Inuktitut | No | No | Una |

Gender, Sexuality, and Language

The LGBT community in Canada is not only diverse in gender and sexual identities, but also linguistically. Canada is a highly multilingual society, and so too are LGBT Canadians. There are many linguistic challenges for the LGBT community, but dedicated language activists and community members continue to help define inclusive language around for LGBT topics and people. Although the linguistic challenges for LGBT people vary from language to language, the fundamental beliefs in equality and community underlie the creative approaches to word choice in all languages.

![[Men and women have compared and contrasted their ways of speaking since we started speaking]](https://langmusecad.files.wordpress.com/2015/09/toilets_unisex-svg.png?w=300)

![[I am made and remade continually. Different people draw different words from me. - V. Woolf]](https://langmusecad.files.wordpress.com/2015/09/george_charles_beresford_-_virginia_woolf_in_1902.jpg?w=220)

![[Lab at UBC where Professor Babel does her research]](https://langmusecad.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/11745804.jpg)

![[Waveform of my gramma saying, "That's like back in the old days"]](https://langmusecad.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/wave.jpg)